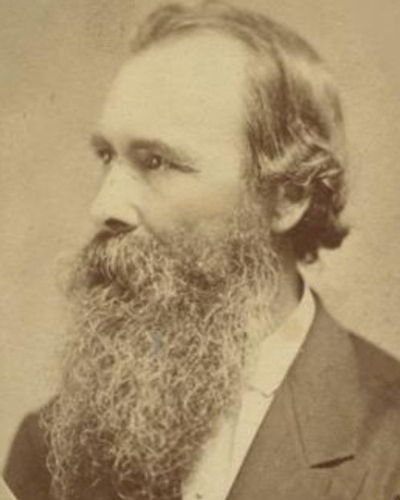

Bovay was born in rural New York in 1818. He received academic and military training at Norwich University in Vermont. After graduating, he taught math and language at several institutions in the area, including the military college at Bristol, PA. In 1846, Bovay was admitted to the bar at Utica New York, where he practiced law and taught math at the New York Commercial Institute. During his formative years in New England, Bovay had been a supporter of the abolitionist movement and a vehement opponent of the expansion of slavery. In 1850, he and his wife (married in 1846) and two-year-old son moved to Ripon, Wisconsin. Ripon was a new community when the Bovays arrived (with only 13 homes in residence), but already a hotbed for progress and political debate. In 1844 Warren Chase, among others, established The Wisconsin Phalanx just outside of Ripon, in an area they named Ceresco (after Ceres, the Roman Goddess of agriculture). Bovay and his family arrived in Ripon shortly after the Phalanx’s disbanding in 1850. He opened an office as an attorney and quickly entered the burgeoning political scene, often leading debates at the general store, post office, or any other place a debate was to be had. He was instrumental in the creation of Ripon College in 1851, where Bovay Hall is named in his honor. Outraged by the further Compromises from Congress regarding the expansion of slavery, and realizing the weakened Whig Party’s disability to challenge the Democrats on the issue, Bovay began calls for a new party as early as 1852 (even going to New York to discuss the idea with Horace Greeley—editor of the influential New York Tribune). He also ran for public office in Ripon, but was defeated by Edwin Judd, a prominent local Whig, in 1853. Democrat Stephen A. Douglas’ introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 angered many in Ripon, Bovay none the least. Bovay called a meeting at the Congregational Church for February 28, 1854 that was heavily attended by the men, women, and children of Ripon. During the meeting, five resolutions were passed—the most of important of which established a new party if the Nebraska Bill were to be passed.

Building off the momentum from the first meeting, Congress’ passing of the Nebraska Bill on March 4, and the freeing of captured slave Joshua Glover by mob from a Milwaukee jail on March 12, Bovay’s March 20, 1854 school house meeting succeeded in the formation of a new political party.

As Bovay himself would later write, “”We went into the little meeting held in a school house Whigs, Free Soilers, and Democrats. We came out of it Republicans and we were the first Republicans in the Union.”