History of the Little White Schoolhouse

Land Ordinance of 1785 – During colonial times, schooling was left up to each of the colonies individually. With the many different religions and ways of life, schooling was difficult to maintain and centralize. In an effort to consolidate schools and make education mandatory, Congress enacted the Land Ordinance of 1785. This ordinance set aside what was known as Section Sixteen in every township in the new Western Territory for the maintenance of public schools. It also allotted section number 29 for the purpose of religion and no more than two townships for a University. The separation of church and state was visible by now with the two entities being in different areas. Public schools were organized to corral the best minds for training for public leadership. Two years later came the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. This ordinance provided land in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions for settlement. (It eventually broke into five states: Michigan, Indiana, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Illinois). Of particular interest is Article 3 of the ordinance, which reads in part: Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged. The point of this document is that education is necessary to become a good citizen and to have a strong government. Children will be encouraged to go to school; however religion is not specifically to be part of the curriculum. Schools then began to form everywhere over the next one-hundred plus years. Instead of township appointed teachers, they were subsidized to an extent by the government and the rest by state taxes. Schools began teaching more than just religion, reading, and spelling. Sciences were part of the new curriculum. Thus, the federal government was able to create a public school system furnished to all children, especially in the new and ever growing West. References: 1. Encyclopedia of American History, Vol. 2, pp. 395-96. Prepared by Kevin VanZant.

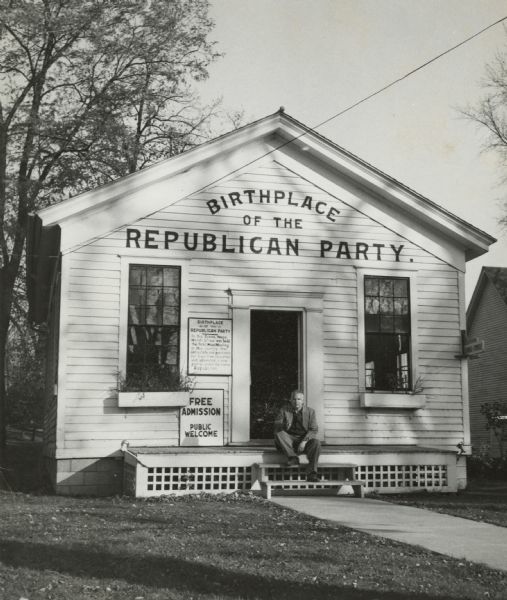

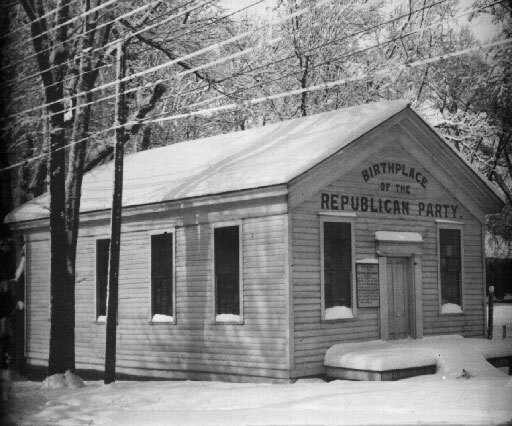

This Schoolhouse: Early settlers of the Ripon/Ceresco area held deep interests in education and political issues. In 1844, the Phalanx of Ceresco had established the first elementary school where classes were held in one room of the original Ceresco Longhouse. Meanwhile in Ripon, residents wanted a school that was more convenient and closer than traveling down to the valley.

By 1850, a second school district was established in Ripon where the first school classes were held in a small structured building on the bank of Silver Creek. A new school building was built three years later, in 1853, on the triangle of Blackburn, Thorne and East Fond du Lac Streets. This school house was Ripon’s first public school and was used as a school building until 1860, where it was moved and remodeled to be a private home for Governor George W. Peck.

This little white schoolhouse is also where a meeting was held to oppose slavery and the Kansas-Nebraska Bill and also where Alvan E. Bovay gave the name “Republican” to a new political party.

The district quickly out grew its one-room schoolhouse and built a new two-story octagon school building, at this time in the 1850s, octagon style architecture was extremely popular, but by 1891, another school was built and the octagon building was abandoned, serving as a private home until it was torn down. There were multiple octagon buildings in the Ripon area and only one still stands today.

Click Here for History About the Mid-19th Century Great Slavery Debate

Slavery in America began when the first African slaves were brought to the North American colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, to aid in the production of such lucrative crops as tobacco. Slavery was practiced throughout the American colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries, and African-American slaves helped build the economic foundations of the new nation. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 solidified the central importance of slavery to the South’s economy.

By the mid-19th century, America’s westward expansion, along with a growing abolition movement in the North, would provoke a great debate over slavery that would tear the nation apart in the bloody American Civil War (1861-65). Though the Union victory freed the nation’s 4 million slaves, the legacy of slavery continued to influence American history, from the tumultuous years of Reconstruction (1865-77) to the civil rights movement that emerged in the 1960s, a century after emancipation.

America’s explosive growth–and its expansion westward in the first half of the 19th century–would provide a larger stage for the growing conflict over slavery in America and its future limitation or expansion.

In 1820, a bitter debate over the federal government’s right to restrict slavery over Missouri’s application for statehood ended in a compromise: Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state, Maine as a free state and all western territories north of Missouri’s southern border were to be free soil. Although the Missouri Compromise was designed to maintain an even balance between slave and free states, it was able to help quell the forces of sectionalism only temporarily.

In 1850, another tenuous compromise was negotiated to resolve the question of territory won during the Mexican War. Four years later, however, the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened all new territories to slavery by asserting the rule of popular sovereignty over congressional edict, leading pro- and anti-slavery forces to battle it out (with much bloodshed) in the new state of Kansas. Outrage in the North over the Kansas-Nebraska Act spelled the downfall of the old Whig Party and the birth of a new, all-northern Republican Party.

In 1857, the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Dred Scott case (involving a slave who sued for his freedom on the grounds that his master had taken him into free territory) effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by ruling that all territories were open to slavery. The abolitionist John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in 1859 aroused sectional tensions even further: Executed for his crimes, Brown was hailed as a martyred hero by northern abolitionists and a vile murderer in the South.

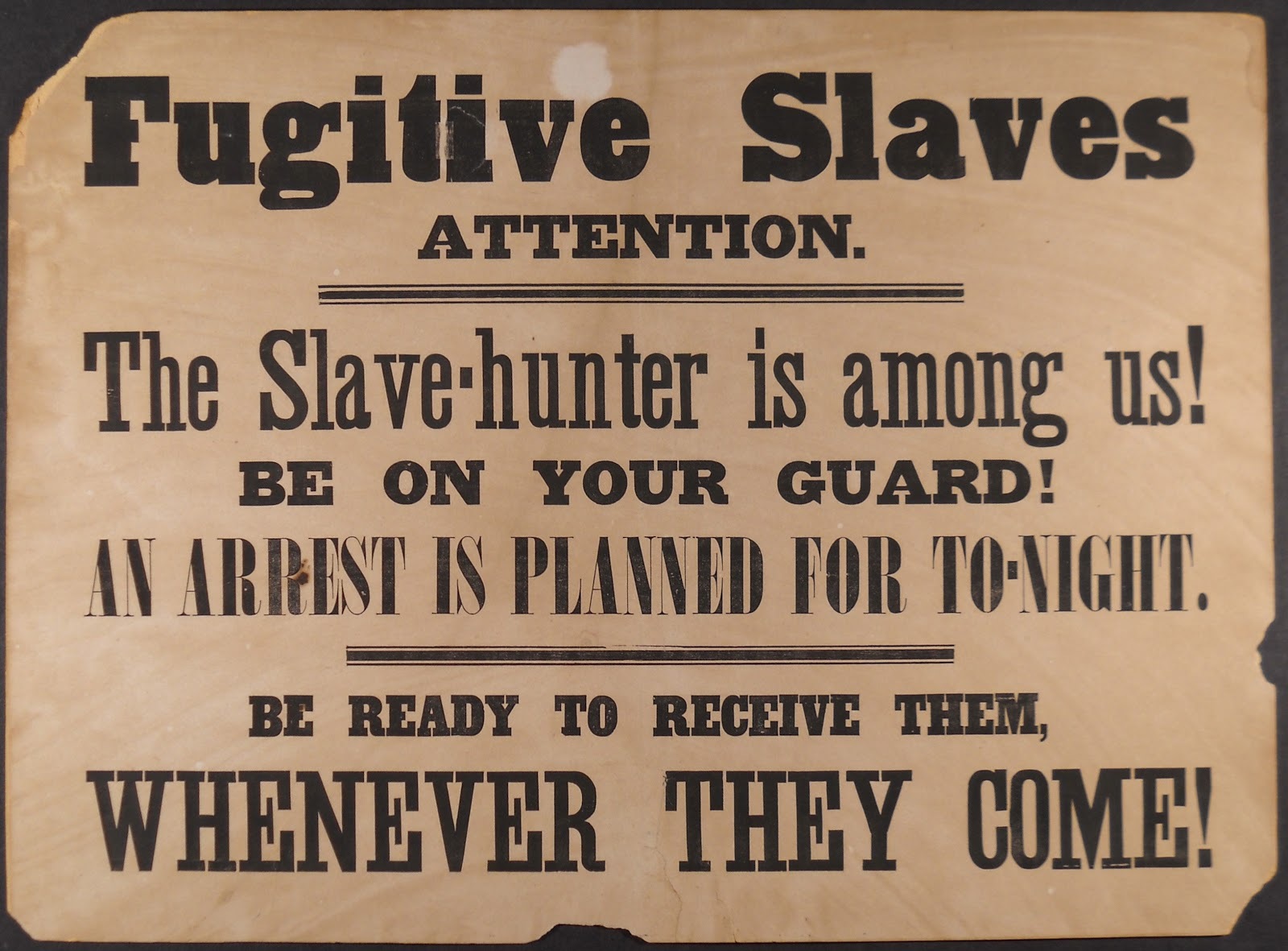

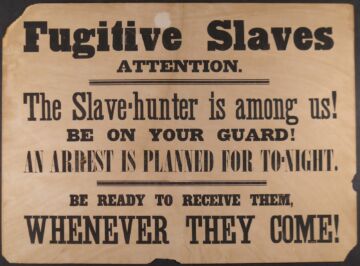

The historical episode familiarly known as “The Booth War” though characterized by a development of fanaticism, was nevertheless, one of the manifestations of the aroused spirit of resistance to the aggressions of the of the slave power, which prevailed in this country at that time. The spirit became manifest in the Northern states in the years immediately following the enactment of the fugitive slave law, in 1850. It gained force on the repeal of the Missouri compromise in 1854, and was materially intensified by the Dred Scott decision in 1857.

It was claimed that the fugitive slave law required every citizen of the United States either to become a slave-catcher at the call of the owner, or to suffer penalties for failure to respond; and that the repeal of the compromise act, followed by the construction given to the Constitution in the Dred Scott decision, made slavery national instead of local, and enabled the slave holder to carry his slaves, like other chattels, under the protection of the Constitution and the laws, into every territory in the Union. By logical sequence, it was apprehended that only one further step was wanting, to establish negro slavery permanently throughout the United States.

Sherman M. Booth was one of the editors of The Free Democrat in Milwaukee. He was an abolitionist of the Garrison and Phillips type, and had the courage of his convictions, but was as impolitic and unpractical as John Brown himself. In season and out of season, he proclaimed the right and duty of every citizen to resist the kidnapping of any man, black or white, for the purpose of carrying him out of state, either to prison or to slavery, until the courts had determined the question of his amenability to the laws of the state demanding him.

To meet, in a measure, the aroused public sentiment, personal liberty laws had been enacted in many of the northern states. In Wisconsin there was a stature authorizing the writ of habeas corpus to issue in favor of persons claimed as fugitive slaves, and requiring the trial of the question of their right to freedom by a jury. The law also required the testimony of at least two witnesses, who must confront the accused in court, to establish the right of the claimant to carry a person to slavery; and a fine and an imprisonment followed the conviction of any person falsely claiming a free negro to be a slave. Furthermore there was a public sentiment in Wisconsin, far more discouraging to slave catchers than the most stringent of statutes could have been.

On the fifteenth day of March, 1854, Booth was arrested on a charge of having aided the escape from C. C. Cotton, deputy United States marshal, of one Joshua Glover, alleged to be a fugitive slave whom the marshal had had in jail in the city of Milwaukee. Booth was held at bail in the sum of $2,000 by United States commissioner, Winfield Smith, but obtained a writ of habeas corpus from the supreme court of Wisconsin, and the case was argued before Associate-Justice A. D. Smith. Byron Paine, afterwards a justice of the same court, defended Booth. The writ of arrest was held to be irregular and was dismissed, and Booth was discharged from custody. The opinion of Judge Smith not only declared the writ irregular, but contained an elaborate and vigorous denial of the constitutionality of the fugitive slave act. At the rehearing before the full bench, during the July term, the decision of Judge Smith was unanimously affirmed. Chief Justice Whiton, who wrote the opinion, concurred with Smith that the act was unconstitutional; and Justice Crawford, in a separate opinion, concurred with both, that the writ upon which Booth was arrested, was defective and void, and all agreed that the prisoner must be discharged. Booth was re-arrested, however, convicted in the United States court on the original charge, and sentenced to thirty days imprisonment, and to be held until he paid a fine of $1,000.

The Birth of the Republican Party …

This simple frame schoolhouse, built in 1853, holds a powerful history. In the Little White Schoolhouse a decision made by a small group of Ripon citizens changed the course of our nation’s history. The birth of the Republican Party brought a dedicated following of individuals together who pledged to organize and fight against the spread of slavery. The spark that brought this action to reality came from the introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, which was brought to Congress in January 1854 by Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois. The bill threatened to extend slavery into the newly opening territories of Kansas and Nebraska. His bill was based on the “Popular Sovereignty” theory that would allow settlers to choose whether slavery would or would not exist within a territory. Douglas hoped the bill would satisfy the interests of both the North and the South.

At the time, a young lawyer named Alvan E. Bovay was living in Ripon. He had come from New York in 1850 to settle here with his family. Bovay was a Whig, and when he lived in New York he became a good friend of Horace Greeley, the influential newspaper publisher of the New York Herald Tribune. Bovay and Greeley had many political interests in common. They were both advocates of land reform, and against the spread of slavery into the newly opening territories.

They maintained their friendship when Bovay moved west. In 1852 when Bovay and Greeley met in New York at the National Whig Convention, Greeley did not support the idea for a new political party. He felt that the Whig candidate would be elected president.

Bovay insisted that the party’s vitality was gone, and its platform no longer commanded the attention of the people. Slavery, was the issue that absorbed the minds of the people. It had become a political and a moral issue. He urged the formation of a new party that would bring together all the anti-slavery forces in the country. When Greeley asked him what name he would give the party, Bovay replied, “Republican” and gave his reasons.